Professional Level – Essentials Module, Paper P3

Business Analysis June 2012 Answers

Tutorial note: the financial ratios given in the following analysis have been calculated using definitions specified in Accounting and

Finance by Peter Atrill and Eddie McLaney. Correct, acceptable alternative ratio calculations will be given credit.

1 (a) The following financial analysis focuses on the profitability and gearing of Hammond Shoes manufacturing division.

Profitability: The effect of cheap imports appears to be reflected in the profitability of the company. Revenues and gross profit

have both fallen significantly in the four years of data given in Figure 1. In 2007 the company reported a gross profit margin

of 23·5% and a net profit margin of 8·2%. This has declined steadily over the period under consideration. The figures for

2009 were 20·0% and 4·7% and for 2011, 17·9% and 2·9% respectively. There has been a general failure to keep costs

under control over this period. Sales have fallen by $150m in four years – almost an 18% decrease. In contrast the cost of

sales has decreased by only $75m, a decrease of about 11·5%. This probably reflects the problem of reducing labour to react

to lower demand, particularly in a country where generous redundancy payments are enforced by law and in an organisation

which sees the employment of local labour as one of its objectives. The Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) has dropped

substantially, from 24·14% in 2007 to 6·45% in 2011.

Gearing: The capital structure of the company has changed significantly in the last four years and this is probably of great

concern to the family who are averse to risk and borrowing. Long-term borrowings have increased dramatically and retained

earnings are falling, reflecting higher dividends being taken by the family. Traditionally, the company has been very low

geared, reflecting the social values of the family. The gearing ratio was only 6·9% in 2007, but has risen to over 22·5% in

2011. During this period, retained profit has fallen and an increasing number of long-term loans have been taken out to

finance activities. Overall, gearing may still appear quite low and indeed this is probably the view of the senior management

of the company. However, the speed of these funding changes is a concern, particularly when trade receivables and trade

payables are considered.

One of the values held by the family is the importance of paying suppliers on time. In Arnland, goods are normally supplied

on 30 days credit. In 2007, Hammond Shoes, on average, exceeded this target, paying on 28 days. However by 2009 this

value had risen to 43 days and by 2011 to 63 days. During the same period, trade receivables, from the selected data

provided, appear to have come down slightly (from 38·65 days in 2007 to 36·50 days in 2011). It is difficult to escape the

conclusion that Hammond Shoes is increasingly using suppliers as a source of free credit on top of the loans they have taken

from the banks. Financing costs have risen significantly over the last four years, affecting profits and also causing the interest

cover ratio to fall dramatically from 14 to 1·33.

The financial analysis essentially supports the descriptive analysis provided by the business analysts. Profits are falling, with

the firm unable to cut costs sufficiently quickly. The company is increasingly dependent on external finance which is likely to

cause disquiet amongst the owning family (on ethical grounds) and may concern suppliers.

Investment analysis:

The two scenarios developed by the senior managers also reflect the pessimism of the company. There seems to be universal

acceptance that in the next three years the company will still experience low sales even after the company invests in the new

production facilities. Beyond that, managers only see a 30% chance of higher sales resulting and this depends upon

favourable changes in the business environment.

For both scenarios, the net benefits of the first three years are $5m per year, giving a total of $15m.

For the next three years, managers suggest that there is a 0·7 chance of continuing low demand, leading to net benefits

staying at $5m per year, giving a further benefit of $15m total, with an expected value of $10·5 ($15m x 0·7). Higher

demand would lead to net benefits of $10m per year, providing a total of $30m, but with an expected value of only $9m

($30m x 0·3).

Thus the expected benefits of the project are only $34·5 ($15m + $10·5m + $9m), which is below the proposed investment

of $37·5m. Only if the second scenario materialises after three years will the investment (in broad terms) have been justified.

This scenario would return $45m.

However, it has to be recognised that the projection only covers the first six years of the new production facilities. The factory

was last updated twenty years ago and so it seems reasonable to expect net profits to continue for many years after the six

years explicitly considered in the scenario, but it must be recognised that predicting net benefits beyond that horizon becomes

increasingly unreliable and subjective.

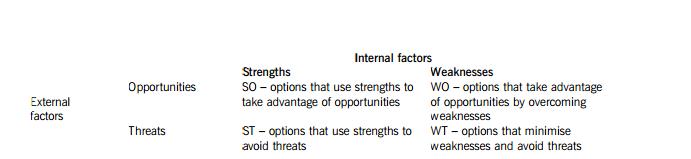

(b) This question does not require the candidate to use a specific framework for generating strategic options. A number of

possibilities exist. The TOWS matrix, the strategy clock and the Ansoff matrix all come to mind. Each of these frameworks has

sufficient facets to generate the number of options or directions required to gain the marks on offer. For the purpose of this

answer, the TOWS matrix is used, because it fits so well with the SWOT analysis produced by the consultants. However, the

focus is on the options generated, not the framework itself and so other frameworks may be as appropriate.

The TOWS matrix is a way of generating directions from an understanding of the organisation’s strategic position. It builds

directly on the work of the SWOT with each quadrant identifying options that address a different combination of the internal

factors (strengths and weaknesses) and external factors (opportunities and threats).