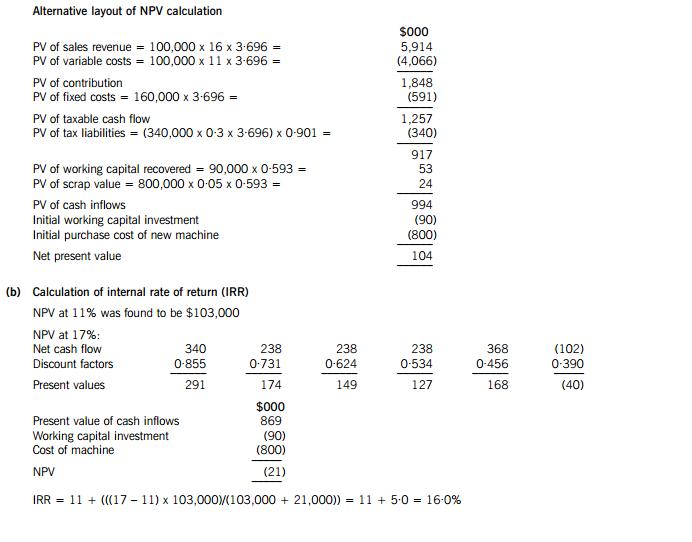

Since the internal rate of return of the investment (16%) is greater than the cost of capital of Warden Co, the investment is

financially acceptable.

Examiner’s note: although the value of the calculated IRR will depend on the two discount rates used in linear interpolation,

other discount rate choices should produce values close to 16%.

(c) Sensitivity analysis indicates which project variable is the key or critical variable, i.e. the variable where the smallest relative

change makes the net present value (NPV) zero. Sensitivity analysis can show where management should focus attention in

order to make an investment project successful, or where underlying assumptions should be checked for robustness.

The sensitivity of an investment project to a change in a given project variable can be calculated as the ratio of the NPV to

the present value (PV) of the project variable. This gives directly the relative change in the variable needed to make the NPV

of the project zero.

Selling price sensitivity

The PV of sales revenue = 100,000 x 16 x 3·696 = $5,913,600

The tax liability associated with sales revenue needs be considered, as the NPV is on an after-tax basis.

Tax liability arising from sales revenue = 100,000 x 16 x 0·3 = $480,000 per year

The PV of the tax liability without lagging = 480,000 x 3·696 = $1,774,080

(Alternatively, PV of tax liability without lagging = 5,913,600 x 0·3 = $1,774,080)

Lagging by one year, PV of tax liability = 1,774,080 x 0·901 = $1,598,446

After-tax PV of sales revenue = 5,913,600 – 1,598,446 = $4,315,154

Sensitivity = 100 x 103,000/4,315,154 = 2·4%

Discount rate sensitivity

Increase in discount rate needed to make NPV zero = 16 – 11 = 5%

Relative change in discount rate needed to make NPV zero = 100 x 5/11 = 45%

Of the two variables, the key or critical variable is selling price, since the investment is more sensitive to a change in this

variable (2·4%) than it is to a change in discount rate (45%).

(d) In real-world capital investment decisions, companies are limited in the funds that are available for investment. However, the

basis for investment decisions should still be to maximise the wealth of shareholders. The NPV decision rule calls for a

company to invest in all projects with a positive net present value, but this is theoretically possible only in a perfect capital

market, i.e. a capital market where there is no limit on the finance available. Since investment funds are limited in the real

world, it is not possible in the real world for a company to invest in all projects with a positive NPV.

The reasons why investment funds are limited in the real world are either external to the company (hard capital rationing) or

internal to the company (soft capital rationing).

Several reasons have been suggested for hard capital rationing, such as that investors may feel that a company is too risky

to invest in, with its credit rating being seen as too low for the amount of investment it needs. Perhaps capital markets may

be depressed, so that there is a general unwillingness by investors to provide funds for capital investment. Capital may be in

short supply due to ‘crowding-out’ as a result of high government borrowing, for example in order to finance a Keynsian

injection of funds into the circular flow of income so as to encourage or assist recovery from an economic recession.

Soft capital rationing may be due to reluctance by a company to raise finance. For example, the amount of funds needed may

be small in relation to the costs of raising the finance: or the company may wish to avoid dilution of control or earnings per

share by issuing new equity; or the company may wish to avoid a commitment to paying fixed interest because it believes

future economic conditions may put its profitability under pressure. Alternatively, the company may limit the funds available

for capital investment in order to encourage competition between potential investment projects, so that only robust investment

projects are accepted. This is the ‘internal capital market’ reason for soft capital rationing.

If a company cannot invest in all projects with a positive NPV, it must ensure that it generates the maximum return per dollar

invested. With single-period capital rationing, where investment funds are limited in the first year only, divisible investment

projects can be ranked in order of desirability using the profitability index. This can be defined either as the NPV divided by

the initial investment, or as the present value of future cash flows divided by the initial investment. The optimal investment

decision for a company is then to invest in the projects in turn, moving from highest profitability index downwards, until all

the funds have been exhausted. This may require partial investment in the last desirable project selected, which is possible

with divisible investment projects.

Where investment projects are not divisible, the total NPV of various combinations of projects must be compared, within the

limit of the investment funds available, in order to select the combination of projects with the highest NPV. This will be the

optimum investment decision. Surplus funds may be left over, but since the highest-NPV combination has been selected, the

amount of surplus funds is irrelevant to the selection of the optimal investment schedule. Investing these surplus funds in a

bank or in the money market would have an NPV of zero.

122 (a) The cash operating cycle is the average length of time between paying trade payables and receiving cash from trade

receivables. It is the sum of the average inventory holding period, the average production period and the average trade

receivables credit period, less the average trade payables credit period. Using working capital ratios, the cash operating cycle

is the sum of the inventory turnover period and the accounts receivable days, less the accounts payable days.

The relationship between the cash operating cycle and the level of investment in working capital is that an increase in the

length of the cash operating cycle will increase the level of investment in working capital. The length of the cash operating

cycle depends on working capital policy in relation to the level of investment in working capital, and on the nature of the

business operations of a company.

Working capital policy

Companies with the same business operations may have different levels of investment in working capital as a result of

adopting different working capital policies. An aggressive policy uses lower levels of inventory and trade receivables than a

conservative policy, and so will lead to a shorter cash operating cycle. A conservative policy on the level of investment in

working capital, in contrast, with higher levels of inventory and trade receivables, will lead to a longer cash operating cycle.

The higher cost of the longer cash operating cycle will lead to a decrease in profitability while also decreasing risk, for example

the risk of running out of inventory.

Nature of business operations

Companies with different business operations will have different cash operating cycles. There may be little need for inventory,

for example, in a company supplying business services, while a company selling consumer goods may have very high levels

of inventory. Some companies may operate primarily with cash sales, especially if they sell direct to the consumer, while other

companies may have substantial levels of trade receivables as a result of offering trade credit to other companies.