Observe the criticisms of nearly any major public education system in the world, and a

few of the many complaints are more or less universal. Technology moves faster

than the education system. Teachers must teach at the pace of the slowest

student rather than the fastest. And--particularly in the United States--grade

school children as a group don’t care much for, or excel at, mathematics. So

it’s heartening to learn that a new kind of “classroom of the future” shows

promise at mitigating some of these problems, starting with that fundamental

piece of classroom furniture: the desk.

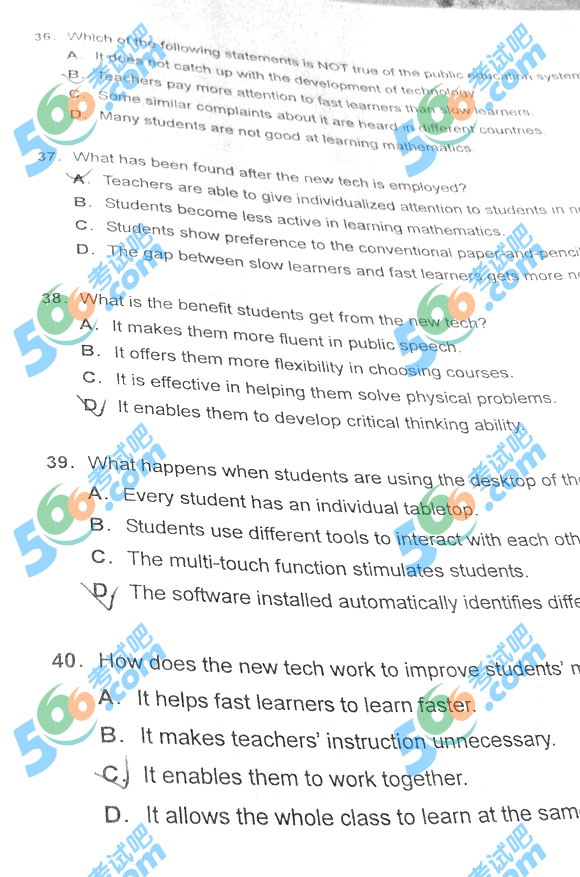

AUK study involving roughly 400 students, mostly aged 8-10 years, and a newgeneration of multi-touch, multi-user, computerized desktop surfaces is showingthat over the last three years the technology has appreciably boosted students’math skills compared to peers learning the same material via the conventionalpaper-and-pencil method. How? Through collaboration, mostly, as well as bygiving teachers better tools by which to micromanage individual students whoneed some extra instruction while allowing the rest of the class to continuemoving forward.

Science,Clay Dillow, classroom of the future, education, engineering, math,mathematics, SynergyNetTraditional instruction still shows respectable efficacyat increasing students fluency in mathematics, essentially through memorizationand practice--dull, repetitive practice. But the researchers have concluded thatthese new touchscreen desks boost both fluency and flexibility--the criticalthinking skills that allow students to solve complex problems not simplythrough knowing formulas and devices, but by being able to figure out what thereal problem is and the most effective means of stripping it down and solvingit.

Onereason for this, the researchers say, is the multi-touch aspect of thetechnology. Students working in the next-gen classroom can work together at thesame tabletop, each of them contributing and engaging with the problem as partof a group. Known as SynergyNet, the software uses computer vision systems thatsee in the infrared spectrum to distinguish between different touches ondifferent parts of the surface, allowing students to access and use tools onthe screen, move objects and visual aids around on their desktops, andotherwise physically interact with the numbers and information on theirscreens. By using these screens collaboratively, the researchers say, thestudents are to some extent teaching themselves as those with a stronger graspon difficult concepts pull other students forward along with them.