| 商家名称 | 信用等级 | 购买信息 | 订购本书 |

|

Git版本控制管理(影印版)(罗力格著) |  |

|

|

Git版本控制管理(影印版)(罗力格著) |  |

《Git版本控制管理(影印版)》你将会:

学习如何在多种真实开发环境中使用Git

洞察Git的常用案例、初始任务和基本功能

理解如何在集中和分布式版本控制中使用Git

使用Git管理补丁、差异、合并和冲突

获得诸如重新定义分支(rebasing)、钩子(hook)以及处

理子模块(子项目)等的高级技巧

学习如何结合使用Git与subversion

这是一本应该随身携带的书。

——Don Marti 编辑、记者以及会议主席

作者:(美国)罗力格(Jon Loeliger)

罗力格,是一位自由职业的软件工程师,致力于Linux、U-Boot和Git等开源项目。他曾在Linux World等诸多会议上公开讲授Git,还为《Linux Magazine》撰写过数篇关于Git的文章。

Preface

1.Introduction

Background

The Birth of Git

Precedents

Time Line

What's in a Name?

2.Installing Git

Using Linux Binary Distributions

Debian/Ubuntu

Other Binary Distributions

Obtaining a Source Release

Building and Installing

Installing Git on Windows

Installing the Cygwin Git Package

Installing Standalone Git (msysGit)

3.Getting Started

The Git Command Line

Quick Introduction to Using Git

Creating an Initial Repository

Adding a File to Your Repository

Configuring the Commit Author

Making Another Commit

Viewing Your Commits

Viewing Commit Differences

Removing and Renaming Files in Your Repository

Making a Copy of Your Repository

Configuration Files.

Configuring an Alias

Inquiry

4.Basic Git Concepts

Basic Concepts

Repositories

Git Object Types

Index

Content-Addressable Names

Git Tracks Content

Pathname Versus Content

Object Store Pictures

Git Concepts at Work

Inside the .git directory

Objects, Hashes, and Blobs

Files and Trees

A Note on Git's Use of SHA1

Tree Hierarchies

Commits

Tags

5.File Management and the Index

It's All About the Index

File Classifications in Git

Using git add

Some Notes on Using git commit

Using git commit ——all

Writing Commit Log Messages

Using git rm

Using git mv

A Note on Tracking Renames

The .gitignore File

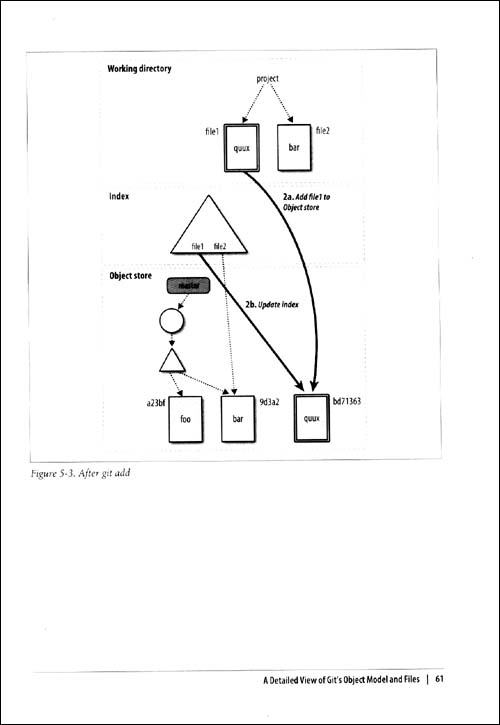

A Detailed View of Git's Object Model and Files

6.Commits

Atomic Changesets

Identifying Commits

Absolute Commit Names

refs and symrefs

Relative Commit Names

Commit History

Viewing Old Commits

Commit Graphs

Commit Ranges

Finding Commits

Using git bisect

Using git blame

Using Pickaxe

7. Branches

Reasons for Using Branches

Branch Names

Dos and Don'ts in Branch Names

Using BrancheS

Creating Branches

Listing Branch Names

Viewing Branches

Checking Out Branches

A Basic Example of Checking Out a Branch

Checking Out When You Have Uncommitted Changes

Merging Changes into a Different Branch

Creating and Checking Out a New Branch

Detached HEAD Branches

Deleting Branches

8.Diffs

Forms of the git diff Command

Simple git diff Example

git diff and Commit Ranges

git diff with Path Limiting

Comparing How Subversion and Git Derive dills

9. Merges

Merge Examples

Preparing for a Merge

Merging Two Branches

A Merge with a Conflict

Working with Merge Conflicts

Locating Conflicted Files

Inspecting Conflicts

How Git Keeps Track of Conflicts

Finishing Up a Conflict Resolution

Aborting or Restarting a Merge

Merge Strategies

Degenerate Merges

Normal Merges

Specialty Merges

Merge Drivers

How Git .Thinks About Merges

Merges and Git's Object Model

Squash Merges

Why Not Just Merge Each Change One by One?

10. Altering Commits

Caution About Altering History

Using git reset

Using git cherry-pick

Using git revert

reset, revert, and checkout

Changing the Top Commit

Rebasing Commits

Using git rebase -i

rebase Versus merge

11. Remote Repositories

Repository Concepts

Bare and Development Repositories

Repository Clones

Remotes

Tracking Branches

Referencing Other Repositories

Referring to Remote Repositories

The refspec

Example Using Remote Repositories

Creating an Authoritative Repository

Make Your Own origin Remote

Developing in Your Repository

Pushing Your Changes

Adding a New Developer

Getting Repository Updates

Remote Repository Operations in Pictures

Cloning a Repository

Alternate Histories

Non-Fast-Forward Pushes

Fetching the Alternate History

Merging Histories

Merge Conflicts

Pushing a Merged History

Adding and Deleting Remote Branches

13.Patches

14.Hooks

15.Combining Projects

16.Using Git with Subversion Repositories

lndex

Audience

While some familiarity with revision control systems will be good background material,a reader who is not familiar with any other system will still be able to learn enoughabout basic Git operations to be productive in a short while. More advanced readersshould be able to gain insight into some of Git's internal design and thus master someof its more powerful techniques.The main intended audience for this book should be familiar and comfortable with theUnix shell, basic shell commands, and general programming concepts.

Assumed Framework

Almost all examples and discussions in this book assume the reader has a Unix-likesystem with a command-line interface. The author developed these examples on Debian and Ubuntu Linux environments. The examples should work under other environments, such as Mac OS X or Solaris, but the reader can expect slight variations.A few examples require root access on machines where system operations are needed.Naturally, in such situations you should have a clear understanding of the responsibilities of root access.

Book Layout and Omissions

This book is organized as a progressive series of topics, each designed to build uponconcepts introduced earlier. The first 10 chapters focus on concepts and operationsthat pertain to one repository. They form the foundation for more complex operationson multiple repositories covered in the final six chapters.If you already have Git installed or have even used it briefly, you may not need theintroductory and installation information in the first two chapters, nor even the quicktour presented in the third chapter.

插图:

It's important to see Git as something more than a version control system: Git is acontent tracking system. This distinction, however subtle, guides much of the design ofGit and is perhaps the key reason Git can perform internal data manipulations withrelative ease. Yet this is also perhaps one of the most difficult concepts for new usersof Git to grasp, so some exposition is worthwhile.Git's content tracking is manifested in two critical ways that differ fundamentally fromalmost all other* revision control systems.

First, Git's object store is based on the hashed computation of the contents of its objects,not on the file or directory names from the user's original file layout. Thus, when Gitplaces a file into the object store, it does so based on the hash of the data and not onthe name of the file. In fact, Git does not track file or directory names, which are asso-ciated with files in secondary ways. Again, Git tracks content instead of files.If two separate files located in two different directories have exactly the same content,Git stores a sole copy of that content as a blob within the object store. Git computesthe hash code of each file according solely to its content, determines that the files havethe same SHA1 values and thus the same content, and places the blob object in theobject store indexed by that SHA1 value. Both files in the project, regardless of wherethey are located in the user's directory structure, use that same object for content.If one of those files changes, Git computes a new SHA1 for it, determines that it is nowa different blob object, and adds the new blob to the object store. The original blobremains in the object store for the unchanged file to use.

Second, Git's internal database efficiently stores every version of every file——not theirdifferences——as files go from one revision to the next. Because Git uses the hash of afile's complete content as the name for that file, it must operate on each complete copyof the file. It cannot base its work or its object store entries on only part of the file'scontent, nor on the differences between two revisions of that file.

相关阅读:

更多图书资讯可访问读书人图书频道:http://www.reAder8.cn/book/